Joan Massagué fondly recalls his first encounter with Jerard Hurwitz in 1989. Dr. Massagué was being recruited to chair the Sloan Kettering Institute’s Cell Biology Program and was making the rounds during the interview process. He walked into the office of Dr. Hurwitz, already a molecular biology legend, and introduced himself.

Dr. Massagué, now Director of SKI, expected a few opening pleasantries, followed by questions about his research plans and ideas on building a new cell biology program. But Dr. Hurwitz wasted no time.

“He looked me in the eye, smiled warmly, and said, ‘So what are you going to do?’” Dr. Massagué recalls. “Warm yet tough, rigorous, straight to the point — that pretty much sums up his character. He would always cut to the chase.”

Dr. Hurwitz, or Jerry to his colleagues and friends, died last week at age 90. A world-renowned molecular biologist, he focused on the biosynthesis of DNA and RNA. He was among those who discovered RNA polymerase, the enzyme that transcribes DNA into messenger RNA. His pivotal studies of the enzymes that drive DNA replication led to a general understanding of how the genome is replicated in dividing cells. This work helped make advances in genetic engineering possible, including the ability to splice and copy DNA.

He is remembered with great admiration and affection by his SKI colleagues, not only for his monumental achievements but also his zeal for bench science that never waned, even at the end of his life.

“There are very few people who could match the number and significance of the contributions he made in biochemistry,” says molecular biologist Kenneth Marians. “For many enzymes that people now use routinely, I’m sure they have no idea that Jerry was one of the people who discovered them.”

Dr. Hurwitz came to Memorial Sloan Kettering in 1984 as Chair of SKI’s Molecular Biology Program. He went on to serve as SKI’s Vice Chair from 1991 to 2003. At the time of his death, he was an emeritus member of SKI in the Molecular Biology Program.

Unflagging Research Focus

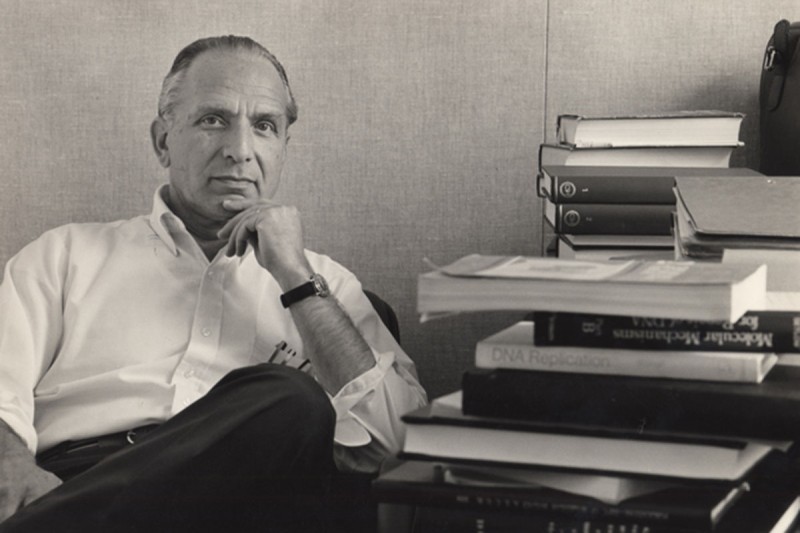

Dr. Hurwitz’s intense scientific focus was reflected in work that spanned more than six decades, beginning in the 1950s and continuing until his final year. After stepping down from his administrative roles at SKI, he continued with his laboratory research.

“At age 85, when most colleagues are retiring or have already done so, he obtained a new five-year National Institutes of Health grant and decided to spend the last years of his career as an active scientist,” Dr. Massagué says. “To the very day that grant ended last spring, he was behind the bench doing experiments with his own hands. That is extremely rare these days, and very inspiring to young investigators to see that passion for science.”

Dr. Hurwitz mentored many junior scientists who have gone on to distinguished careers of their own. At Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the 1960s, he helped train David Baltimore, who shared the 1975 Nobel Prize in Medicine for work on the enzyme reverse transcriptase, and Stanley Cohen, who — together with Herbert Boyer — demonstrated the possibility of producing recombinant DNA in bacteria in 1973.

Dr. Marians was a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Hurwitz’s laboratory at Albert Einstein in the 1970s and was recruited to SKI by Dr. Hurwitz when he moved to MSK to set up shop. He says his former mentor was deeply invested in helping young scientists and in scientific rigor.

“The most important idea he passed on to his trainees was that you don’t want to try to fit the data to your model,” Dr. Marians says. “That can be a hard lesson, but Jerry was very up front about it. If your data was no good, he let you know it in no uncertain terms.”

This discipline and exactitude was especially important in the period when Dr. Hurwitz joined SKI. He was at Albert Einstein in the early 1980s, when physician-scientist Paul Marks became MSK President. Dr. Marks and SKI Director Richard Rifkind recruited Dr. Hurwitz to SKI along with Ora Rosen, a world expert in the biology of hormones and how they dictate cell growth.

Dr. Marks had been looking for ways to transform oncology into a research-driven science. It was a critical time for SKI, which Dr. Marks sought to build into a leader in molecular biology. Drs. Hurwitz and Rosen elevated the stature of the institution through their work. Dr. Rosen helped clone the gene for the human insulin receptor, shedding light on the understanding of diabetes and cancer in the process. The two scientists wed after coming to MSK and remained married until Dr. Rosen died in 1990. (Dr. Hurwitz later remarried.)

“At the time, outstanding scientists were not thinking about coming to work at SKI. It was not a place that would typically have come up,” Dr. Marians explains. “When Jerry and Ora moved here, it began the process of building up SKI to recruiting first-rank scientists and making it what it is now.”

Always in the Vanguard

From early in his career, Dr. Hurwitz was at the forefront of groundbreaking research on DNA and RNA. In 1956, he joined the microbiology department at Washington University in St. Louis, which was chaired by Arthur Kornberg, whose research accomplishments in enzyme chemistry were already legendary. (Dr. Kornberg won the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering how DNA is synthesized.) Dr. Hurwitz began looking for RNA polymerase while he was at Washington University, continuing those efforts after moving to New York University in 1958, where he was a professor of microbiology until 1963.

In 1960, Dr. Hurwitz reported the isolation of RNA polymerase activity from extracts of Escherichia coli — it was, perhaps, his greatest scientific achievement.

In 1965, he moved to Albert Einstein, where he continued his research for the next two decades as a professor and the chair of the department of developmental biology and cancer. In the early 1970s, he clarified the DNA replication process in bacteria and identified many of the enzymes that are required for this process to work. Dr. Hurwitz’s later research also shed light on how the cell cycle is regulated and the structure and assembly of the protein complexes involved in initiating cell replication.

Dr. Hurwitz was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1974. He received numerous awards throughout his career, including the Eli Lilly Award in Biochemistry in 1962, a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1968, the Institut Pasteur Hazen Lectureship in 1972, and the New York Academy of Science’s Louis and Bert Freeman Foundation Prize for Research in Biochemistry in 1982. He was a longtime American Cancer Society Research Professor.

He continued to set the standard for excellence at SKI through the final year of his life.

“He’s revered by all of those who had the privilege to know him, and it is an inspiration to pay homage to someone who did so much for so long, both for science and for our institution,” Dr. Massagué says.