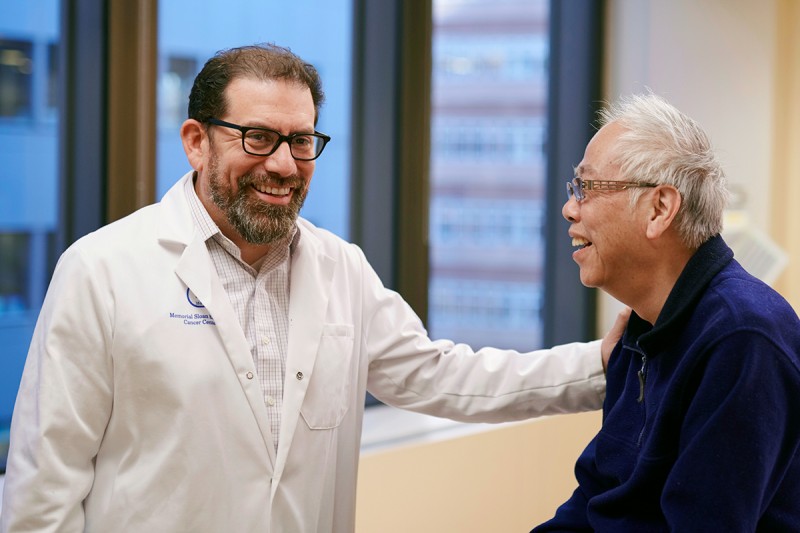

Dr. Luis Diaz Jr. has made important discoveries about genetic mutations in tumors that predict which patients will respond well to immunotherapy.

What Is Immunotherapy Cancer Treatment

Immunotherapy is a form of cancer treatment. Most cancer treatments use drugs or radiation to target cancer cells directly. Immunotherapy instead boosts your immune system’s natural ability to fight cancer. Your immune system attacks cancer cells, much the same way it attacks bacteria or viruses.

Cancer immunotherapy has greatly improved in recent years. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) is always working to make cancer immunotherapy even better.

Researchers are exploring whether immunotherapy can be used for many kinds of cancer. MSK patients can join research studies, also known as clinical trials. You may be able to get early access to new and promising immunotherapy treatments.

What are the types of immunotherapy?

There are 3 main types of immunotherapy. The kind of immunotherapy you get is based on the type of cancer, tumor genetics, and other things.

Checkpoint Inhibitors

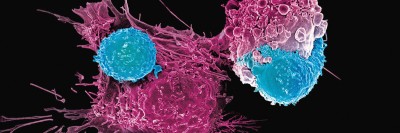

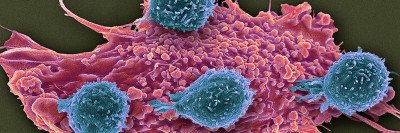

Checkpoint inhibitors work by releasing a natural brake on your immune system. It lets immune cells called T cells recognize and attack tumors.

Adoptive Cell-Based Therapy

These are natural or engineered versions of your own immune cells. We can grow a large number of these cells in a lab. We then put them back into your body. Having more of these cells is like having a bigger army to naturally fight cancer. These therapies sometimes are called living drugs and includes CAR T and TIL:

-

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy

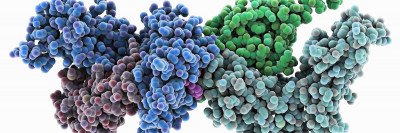

Chimeric (ky-MEER-ik) antigen (AN-tih-jen) receptor, or CAR T cell therapy, is a type of immunotherapy. It’s when scientists in a lab change the genes of your own immune cells. The cells can then make a new protein that turns them into supercharged cancer fighters. -

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TIL)

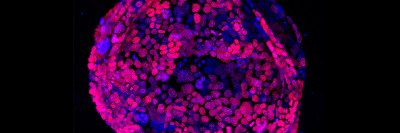

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (LIM-foh-sites) are known as TIL, pronounced “till.” They’re a special type of white blood cell that have infiltrated (invaded) a tumor in your body. TIL therapy takes these immune cells from inside the tumor. It grows them in large numbers and then puts them back into your body.

Cancer Vaccines

Cancer vaccines, like all vaccines, work by training your immune system to defend your body against possible threats. The threats can be from foreign invaders, like a virus, or from abnormal cells, like cancer. Cancer vaccines are made to either prevent or treat cancer. They train the immune system to find harmful cells that have markers, called antigens.

How is immunotherapy given to someone?

Immunotherapy can be administered in 2 ways:

- Drugs that can be used off-the-shelf, rather than made just for each person. These medicines often are given intravenously (IV), which means in the vein. Pembrolizumab and ipilimumab are common examples.

- Cell-based therapy, which is when we remove and change your own immune cells. We then reinfuse (put them back) into your body intravenously to treat cancer.

Which cancers can immunotherapy treat?

Immunotherapy works well for cancers with markers that the immune system can recognize. Here are some examples:

- Cancers with many genetic changes (mutations or variants). These are good targets for immunotherapy because they do not look like normal cells. Some cancers have many mutations from genetic damage. For example, sunlight can harm a cell’s genes and cause melanoma. Cigarette smoking can trigger genetic changes and cause lung cancer. Genetic conditions can make it more likely cells will mutate and cause cancer. One example is some types of colon cancer.

- Cancers with high levels of PD-L1 expression. Some cancers make a protein called PD-L1. This protein can step on an immune cell’s brakes and shut down the immune system’s response. Certain cancers with high amounts of PD-L1 are good candidates for immunotherapy drugs that target PD-1. Examples are the drugs pembrolizumab and nivolumab.

- Cancers with certain markers on their surface. These markers let CAR T cells see the cancer cells as a threat. This makes the cancer more likely to respond to CAR T immunotherapy. One example is the surface marker CD19 on B cell leukemias.

What are the side effects of immunotherapy?

The most common side effects are from the immune system overreacting to normal tissues. Side effects include:

- Skin problems, such as a rash or itching

- Chills, fatigue (feeling very tired), and other flu-like symptoms

- Gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea (loose poop)

- Pain from joint inflammation (swelling)

Most side effects can be managed safely if treated early. Sometimes, side effects can cause harm if they’re not treated and they involve organs, such as the lungs.

MSK doctors are experts in caring for people who have side effects from immunotherapy.

Can the immune system stop cancer on its own?

Your immune system keeps you safe from many threats. This includes infectious bacteria and viruses, and also cancer. Immune cells attack cells that look foreign or harmful. This includes mutated cells that can cause cancerous tumors. Your immune system often stops cancer from starting or growing.

However, cancer cells can trick the immune system so it will not attack them. Immune cells have brakes that are there to stop them from attacking healthy cells. Cancer cells can step on those brakes. Cancer cells also can change the tumor microenvironment in nearby tissue so that it’s hostile to immune cells.

Immunotherapy can help your immune system overcome these tricks and destroy the cancer.

Is there anything you can do to boost your immune system so immunotherapy works better?

There’s nothing you can really do to make sure immunotherapy works well. Some research shows that people do better when they’re keeping a healthy gut microbiome. You can do that by eating a nutritious diet high in plant fiber. Avoid antibiotics you don’t really need, and avoid probiotics.

What percentage of people with cancer can immunotherapy help?

It depends on the kind of cancer. In general, immunotherapy helps:

- Between 15 and 30 out of every 100 people who have common solid tumors. This includes lung, bladder, and kidney cancer.

- Between 45 and 60 out of every 100 people with certain skin cancers, as well as people with solid tumors that have a type of mutation called MMRd/MSI-high.

Why does immunotherapy stop working?

Immunotherapies may stop working when cancer cells change and can escape immune cells. Often, they lose the marker or markers that immune cells use to identify them. This is called antigen escape or immune escape.

Cancer and the immune system are always in a battle. Immunotherapy can make the immune system have a stronger response so it can control cancer as long as possible.