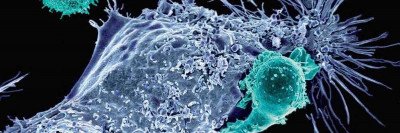

Scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering announced today that they have built a new model of genetically engineered immune cells, ones with powerful “armor” that may allow them to fight solid tumors.

The new cells combine two of the most promising types of immunotherapy — chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and checkpoint inhibitors — into one sleek package. CAR T cells are genetically engineered versions of a patient’s own immune cells built to find and kill cancer cells. Checkpoint inhibitors take the brakes off immune cells, allowing them to fight cancer for longer.

“We took a step back and asked, ‘How can we make CAR T cells better?’ ” explains Renier Brentjens, Director of the Cellular Therapeutics Center at MSK and one of the pioneers of CAR therapy. “That’s when we decided to try to combine these two promising approaches.”

By themselves, CAR T cells have shown remarkable success in treating certain blood cancers. So far, however, they have not been able to vanquish solid tumors. Checkpoint inhibitors, on the other hand, have proved remarkably effective at empowering the immune system to fight a variety of solid tumors. But they can produce severe immune-related side effects.

By engineering checkpoint inhibitors directly into the CAR T cell itself, the MSK team believes they can limit the side effects of these drugs while taking advantage of their powerful immune-stimulating capabilities.

Better Persistence, Better Results

The newly designed CAR T cells secrete a mini version of a checkpoint-blocking antibody. This antibody is similar to the drugs nivolumab (Opdivo®) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda®), which are approved for the treatment of several types of cancer. The antibody binds to a protein called PD-1 that acts like a brake on immune cells. The antibody releases this brake, allowing the CAR T cells and surrounding immune cells to better fight the disease.

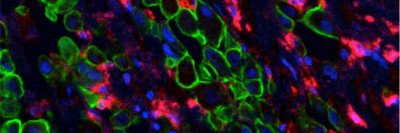

The MSK team — including lab members Sarwish Rafiq, Oladapo Yeku, and Hollie Jackson — made two versions of this armored CAR. One recognizes a molecule called CD19, which is found on certain blood cancers. The other recognizes MUC16, which is found on some ovarian cancers and pancreatic cancers. Then they tested the cells in several different mouse models of cancer.

In all cases, including mouse models of solid tumors, the team found that the armored CARs persisted longer in the body than standard CARs. And they produced better results — namely, the mice lived significantly longer.

What’s more, because the checkpoint drugs were released directly into the tumor, they activated nearby T cells, creating a helpful bystander effect. In other words, the CAR T cells were able to enlist the help of other T cells to fight the tumor.

Finally, the team found that the levels of the PD-1 antibody were low in the circulating blood, indicating that the checkpoint molecules were not spreading far beyond the site of the tumor. That’s important because it means there will be fewer systemic side effects.

“This proves — at least in a mouse model — that we can now have our cake and eat it too,” Dr. Brentjens says.

He emphasizes that the approach can be thought of as providing a new platform for CAR therapy. “We can build CAR T cells to secrete a variety of different molecules, tailored to the needs of the patient,” he says. “It’s not just limited to this one drug.”

The MSK team hopes to translate their new armored CAR platform to the clinic and is in the process of designing clinical trials.

A paper describing the approach appears today in the journal Nature Biotechnology.