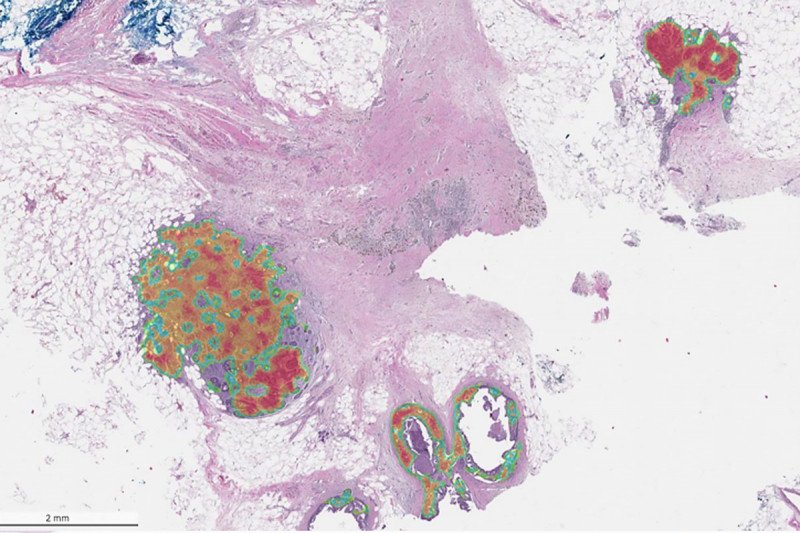

Shades of red, orange, and green indicate Paige Breast Alpha detection of invasive ductal (middle left, top right) and in-situ (bottom right) carcinoma of the breast.

Among doctors, pathology is often considered the backbone of medicine. Those who study pathology — pathologists — are the ones who actually diagnose diseases. They do this by looking at sections of tissue under a microscope, analyzing the shape and color of cells, noting unusual features, and measuring the size of growths or other oddities.

Pathologists at major cancer centers like Memorial Sloan Kettering usually specialize in identifying particular types of cancer — breast or prostate cancer, for instance. Because pathologists routinely see so many examples of each cancer, they are experts at making accurate diagnoses, including sub-typing and staging.

Now, with the help of machine learning, MSK pathologists are hoping to automate some of this painstaking detective work, with the ultimate goal of training computers to see tumor features that human eyes cannot, permitting better and faster detection of cancer.

The secret sauce is the massive collection of pathology slides that MSK has accumulated in its 136-year history and converted to digital form.

“Because we have this enormous repository of digitized slides — probably one of the largest and complex in the world — we can train computers using a truly unparalleled dataset,” says Matthew Hanna, Director of Digital Pathology Informatics at MSK. “In partnership with Paige, a global leader in digital diagnostics that spun out of MSK in 2017, MSK is really helping to spearhead this effort.”

On December 10, at this year’s virtual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, Dr. Hanna presented results from a test of a digital pathology platform called Paige Breast Alpha. Trained on nearly 26,000 slides from 6,000 patients with breast cancer who were treated at MSK, the platform is designed to notice the presence or absence of certain cancerous features and thereby detect and classify breast cancer.

He and his colleagues found that Paige Breast Alpha was able to detect malignancy and other suspicious changes with an overall sensitivity of 96% — meaning that it was incorrect just four times out of every 100.

The technology is still experimental and is not being used to guide patient care at MSK, but that day is likely not far off, Dr. Hanna says.

Democratizing Expertise

Beyond improving care at MSK, the team hopes Paige Breast Alpha will help improve cancer care at community hospitals by exporting MSK’s expertise to pathologists around the country.

“Unlike larger academic centers, many pathologists in community centers are generalists,” Dr. Hanna says. “They must be jacks-of-all-trades and cover a significantly wider diagnostic breadth. That’s where a tool like Paige Breast Alpha, which was trained on MSK’s high-quality data, can really make a difference.”

As powerful as it is, the technology will not replace human pathologists any time soon, nor is it intended to.

“Detecting pathological changes on slides is just one task out of the many that pathologists must do to make an accurate diagnosis,” Dr. Hanna says. “They must also look for the distance that tumor is from the margins, determine tumor grade and stage, including lymph node involvement, and more.”

But by improving speed and efficiency of this one step, Paige Breast Alpha can help pathologists triage the most urgent cases and be more confident in their diagnoses.

Ultimately, the goal of digital pathology, Dr. Hanna says, is to extend its reach into areas where humans really can’t compete — in being able to provide digital biomarkers that correlate with specific treatment or outcome data.

“So, for example, if one day we are able to say that tumors that look like this responded to this treatment, or tumors that look like that had patient outcomes that were better than these tumors — which look different — that is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Hanna says.